How-to guides¶

This section contains goal-oriented guides on the features of scikit-fem.

Finding degrees-of-freedom¶

Often the goal is to constrain DOFs on a specific part of

the boundary. Currently the main tool for finding DOFs is

get_dofs().

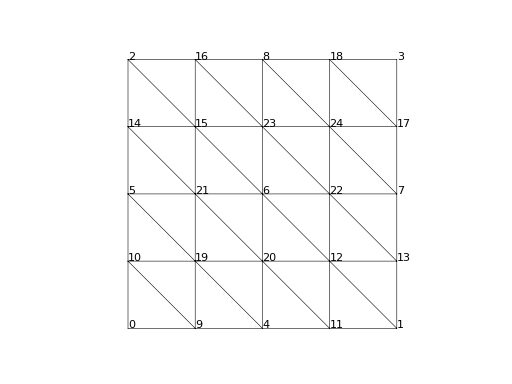

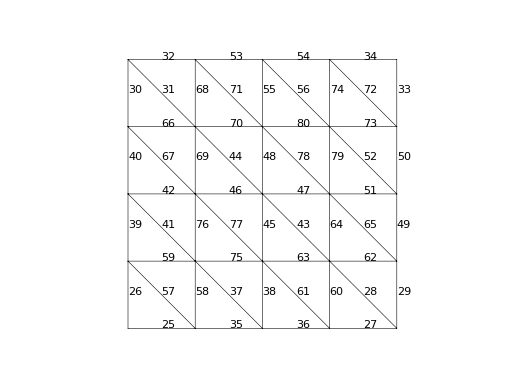

>>> from skfem import MeshTri, Basis, ElementTriP2

>>> m = MeshTri().refined(2)

>>> basis = Basis(m, ElementTriP2())

We can provide an indicator function to

get_dofs() and it will find the

DOFs on the matching facets:

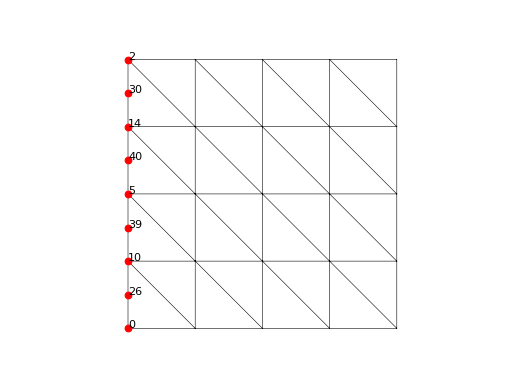

>>> dofs = basis.get_dofs(lambda x: x[0] == 0.)

>>> dofs.nodal

{'u': array([ 0, 2, 5, 10, 14])}

>>> dofs.facet

{'u': array([26, 30, 39, 40])}

This element has one DOF per node and one DOF per facet. The facets have their own numbering scheme starting from zero, however, the corresponding DOFs are offset by the total number of nodal DOFs:

>>> dofs.facet['u']

array([26, 30, 39, 40])

The keys in the above dictionaries indicate the type of the DOF according to the following table:

Key |

Description |

|---|---|

|

Point value |

|

Normal derivative |

|

Partial derivative w.r.t. \(x\) |

|

Second partial derivative w.r.t \(x\) |

|

Normal component of a vector field (e.g., Raviart-Thomas) |

|

Tangential component of a vector field (e.g., Nédélec) |

|

First component of a vector field |

|

Partial derivative of the first component w.r.t. \(x\) |

|

First component of the first component in a composite field |

|

Description not available (e.g., hierarchical or bubble DOF’s) |

An array of all DOFs with the key u can be obtained as follows:

>>> dofs.all(['u'])

array([ 0, 2, 5, 10, 14, 26, 30, 39, 40])

>>> dofs.flatten() # all DOFs, no matter which key

array([ 0, 2, 5, 10, 14, 26, 30, 39, 40])

If a set of facets is tagged, the name of the tag can be passed

to get_dofs():

>>> dofs = basis.get_dofs('left')

>>> dofs.flatten()

array([ 0, 2, 5, 10, 14, 26, 30, 39, 40])

Many DOF types have a well-defined location. These DOF locations can be found as follows:

>>> basis.doflocs[:, dofs.flatten()]

array([[0. , 0. , 0. , 0. , 0. , 0. , 0. , 0. , 0. ],

[0. , 1. , 0.5 , 0.25 , 0.75 , 0.125, 0.875, 0.375, 0.625]])

See Indexing of the degrees-of-freedom for more details.

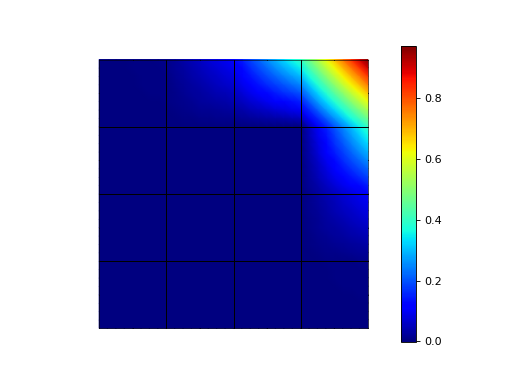

Performing projections¶

We can use \(L^2\) projection to find discrete counterparts of functions or transform from one finite element basis to another. Suppose we have \(u_0(x,y) = x^3 y^3\) defined on the boundary of the domain and want to find the corresponding discrete function which is extended by zero in the interior of the domain. You could explicitly assemble and solve the linear system corresponding to: find \(\widetilde{u_0} \in V_h\) satisfying

However, this is so common that we have a shortcut

project():

>>> import numpy as np

>>> from skfem import *

>>> m = MeshQuad().refined(2)

>>> basis = FacetBasis(m, ElementQuad1())

>>> u0 = lambda x: x[0] ** 3 * x[1] ** 3

>>> u0t = basis.project(u0)

>>> np.abs(np.round(u0t, 5))

array([1.0000e-05, 8.9000e-04, 9.7054e-01, 8.9000e-04, 6.0000e-05,

6.0000e-05, 1.0944e-01, 1.0944e-01, 0.0000e+00, 2.0000e-05,

2.0000e-05, 2.4000e-04, 8.0200e-03, 3.9797e-01, 3.9797e-01,

2.4000e-04, 8.0200e-03, 0.0000e+00, 0.0000e+00, 0.0000e+00,

0.0000e+00, 0.0000e+00, 0.0000e+00, 0.0000e+00, 0.0000e+00])

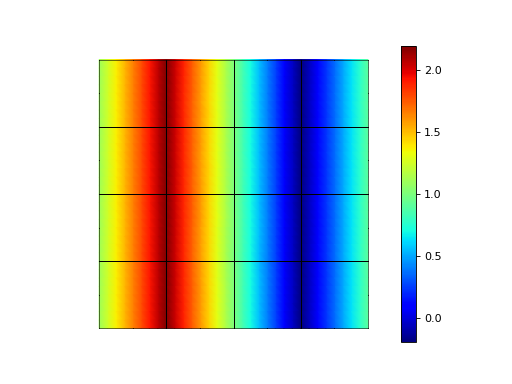

We can also project over the entire domain:

>>> basis = Basis(m, ElementQuad1())

>>> f = lambda x: np.sin(2. * np.pi * x[0]) + 1.

>>> fh = basis.project(f)

>>> np.abs(np.round(fh, 5))

array([1.09848, 0.90152, 0.90152, 1.09848, 1. , 1.09848, 0.90152,

1. , 1. , 2.19118, 1.09848, 0.19118, 0.90152, 0.90152,

0.19118, 1.09848, 2.19118, 1. , 2.19118, 0.19118, 1. ,

2.19118, 0.19118, 0.19118, 2.19118])

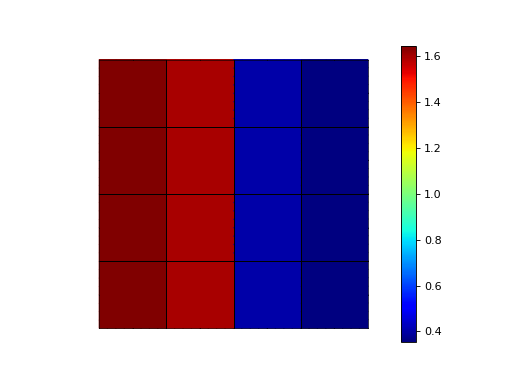

We can project from one finite element basis to another:

>>> basis0 = basis.with_element(ElementQuad0())

>>> fh = basis0.project(basis.interpolate(fh))

>>> np.abs(np.round(fh, 5))

array([1.64483, 0.40441, 0.40441, 1.64483, 1.59559, 0.35517, 0.35517,

1.59559, 1.59559, 0.35517, 0.35517, 1.59559, 1.64483, 0.40441,

0.40441, 1.64483])

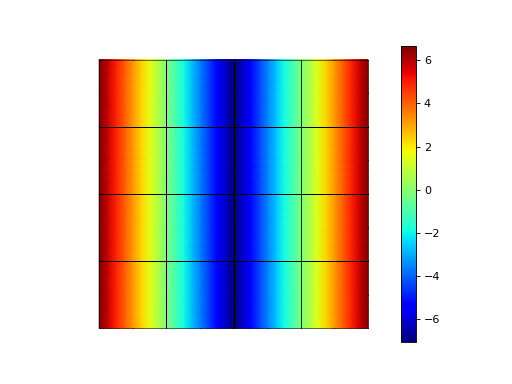

We can interpolate the gradient at quadrature points and project:

>>> f = lambda x: np.sin(2. * np.pi * x[0]) + 1.

>>> fh = basis.project(f) # P1

>>> fh = basis.project(basis.interpolate(fh).grad[0]) # df/dx

>>> np.abs(np.round(fh, 5))

array([6.6547 , 6.6547 , 6.6547 , 6.6547 , 7.04862, 6.6547 , 6.6547 ,

7.04862, 7.04862, 0.19696, 6.6547 , 0.19696, 6.6547 , 6.6547 ,

0.19696, 6.6547 , 0.19696, 7.04862, 0.19696, 0.19696, 7.04862,

0.19696, 0.19696, 0.19696, 0.19696])

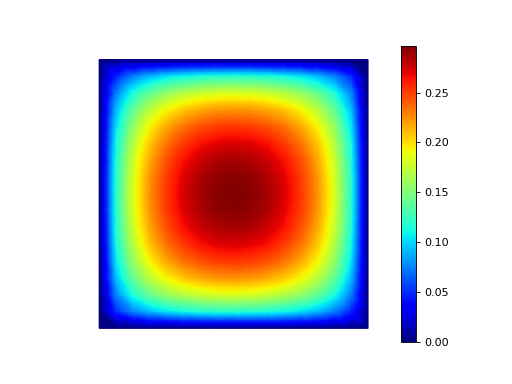

Discrete functions in forms¶

We can use finite element functions inside the form by interpolating them at quadrature points. For example, consider a fixed-point iteration for the nonlinear problem

We repeatedly find \(u_{k+1} \in H^1_0(\Omega)\) which satisfies

for every \(v \in H^1_0(\Omega)\). The bilinear form depends on the previous solution \(u_k\).

>>> import skfem as fem

>>> from skfem.models.poisson import unit_load

>>> from skfem.helpers import grad, dot

>>> @fem.BilinearForm

... def bilinf(u, v, w):

... return (w.u_k + .1) * dot(grad(u), grad(v))

The previous solution \(u_k\) is interpolated at quadrature points using

interpolate() and then provided to

assemble() as a keyword argument:

>>> m = fem.MeshTri().refined(3)

>>> basis = fem.Basis(m, fem.ElementTriP1())

>>> b = unit_load.assemble(basis)

>>> x = 0. * b.copy()

>>> for itr in range(20): # fixed point iteration

... A = bilinf.assemble(basis, u_k=basis.interpolate(x))

... x = fem.solve(*fem.condense(A, b, I=m.interior_nodes()))

... print(round(x.max(), 10))

0.7278262868

0.1956340215

0.3527261363

0.2745541843

0.3065381711

0.2921831118

0.298384264

0.2956587119

0.2968478347

0.2963273314

0.2965548428

0.2964553357

0.2964988455

0.2964798184

0.2964881386

0.2964845003

0.2964860913

0.2964853955

0.2964856998

0.2964855667

Note

Inside the form definition, w is a dictionary of user provided

arguments and additional default keys. By default, w['x'] (accessible

also as w.x) corresponds to the global coordinates and w['h']

(accessible also as w.h) corresponds to the local mesh parameter.

Assembling jump terms¶

The shorthand asm()

supports special syntax for assembling the same form over lists of

bases and summing the result. The form

with jumps \([u] = u_1 - u_2\) and \([v] = v_1 - v_2\) over the interior edges can be split as

and normally we would assemble all of the four forms separately.

We can instead provide a list of bases during a call to skfem.assembly.asm():

>>> import skfem as fem

>>> m = fem.MeshTri()

>>> e = fem.ElementTriP0()

>>> bases = [fem.InteriorFacetBasis(m, e, side=k) for k in [0, 1]]

>>> jumpform = fem.BilinearForm(lambda u, v, p: (-1) ** sum(p.idx) * u * v)

>>> fem.asm(jumpform, bases, bases).toarray()

array([[ 1.41421356, -1.41421356],

[-1.41421356, 1.41421356]])

For an example of practical usage, see Example 7: Discontinuous Galerkin method.